August 29, 2019

East Aurora Native Prepares to Get Vertical with Buffalo’s Central Terminal

I had the opportunity to accompany my former Oakwood Avenue neighbor (mid-1950s) and lifelong friend Kent Diebolt on a tour of Buffalo’s Central Terminal last week. What a privilege. While most visitors are relegated to the outside where they gawk at the deteriorating, but still stately, 270-foot-tall Art Deco icon that watched over Buffalo’s bustling rail lines in the mid-20th century, Kent had the keys and the security code.

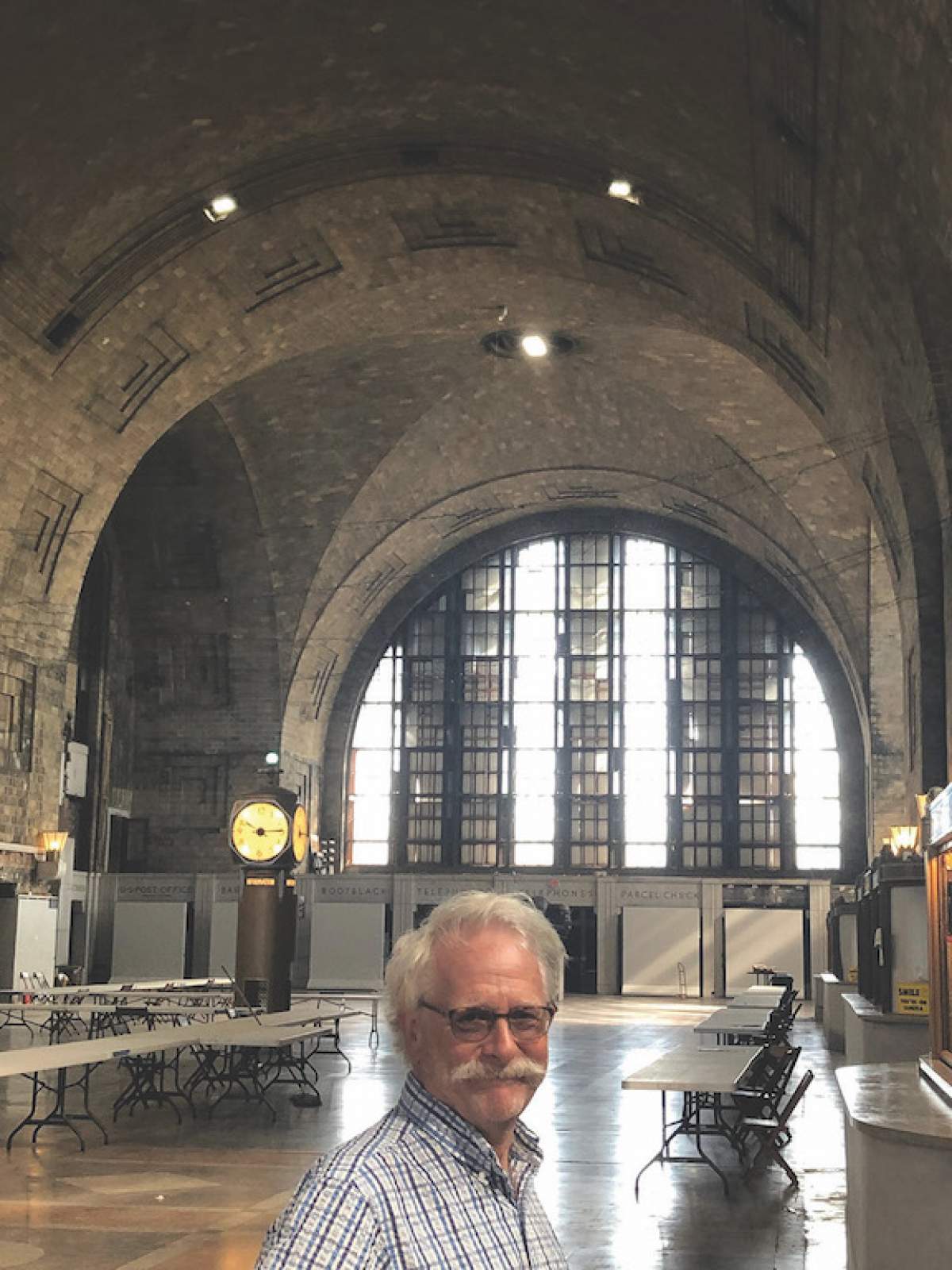

Inside, the building still overwhelmed me, even in its tattered state, with its vaulted arches of ceramic tile forming a rotunda that rises 90 feet above the terrazzo floor and marble paneling. Vestiges of a genteel yesteryear still remain, like a worn sign announcing New York Central’s “Cayuga” departing at 8:30 for Batavia, Rochester and points east; ticket booths with marble counters; the erstwhile dining room as big as an Amtrak station of today but in shambles; and the non-digital clock with a three-foot face, its hands still keeping time.

Kent was not overwhelmed; he was chomping at the bit. He was there to organize his company’s latest job: inspecting the tiles and masonry work in the rotunda so he can advise engineers and contractors who will begin the process of rehabilitating the landmark. “I’ve always wanted to work on this building,” he said, confident that there is finally a plan in place to restore it to its former glory.

Kent Diebolt is the founding partner of Vertical Access, LLC, the Ithaca-based architectural consulting firm that specializes in inspecting buildings, like the train station, where access is a challenge. Using rock climbing techniques and gear—ascending and rappelling on ropes—and, more recently, hydraulic lifts, Kent and his certified rope-access technicians will get to places that might otherwise be inaccessible or require extensive, cost-prohibitive and time-consuming scaffolding arrangements. From their rope-secured or lift-accessed perches, Vertical Access technicians collect data on a building’s condition using cameras and other monitoring devices and input their findings using the proprietary software called TPAS that offers architects, engineers and contractors realistic direct-to-AutoCAD imaging.

“Having our eyes on the surfaces from a rope access beats anything binoculars, cameras or (most recently) drones can do,” said Vertical Access technician, Kristen Olson.

Locals may have already seen Vertical Access in operation without knowing it. If you spotted workers in white coveralls and red helmets descending on ropes from the spires at the old Post Office building (now City Campus of Erie Community College) or Buffalo’s City Hall a few years ago and wondered what they were up to, they were assessing the condition of the masonry work—crumbling stone or brick, faulty mortar, cracked joints—and recommending areas that needed to be repaired in the interest of public safety and the building’s longevity.

Diebolt started Vertical Access back in 1991. After spending his school years in East Aurora (he was a member of the class of ’71 and a part time cashier at Spike Amsler’s Deli; his mother Betsy was involved in the popular teen night club, the Minotaur in the ‘60s), he worked a while in the surveying and nursery fields, earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in plant physiology from Alfred and Cornell, became a carpenter and then went out on his own as a builder in Ithaca. Looking for a niche in the building business, he accepted a friend’s invitation to travel to England in 1991 to help inspect a masonry building using climbing ropes. He hadn’t had a lot of experience climbing, but he took to the task and decided that he might have found his niche.

The success of Vertical Access was hardly a slam-dunk; in fact it was quite a gamble on Diebolt’s part, especially with young children to support. Although rope access inspections are common in Europe, they weren’t very well accepted in the United States, perhaps perceived as more of a gimmick pulled off by rock climbers looking to make a hobby pay. It took a while for Kent to get a foothold, so to speak, with engineers and architects. But as is his style, Diebolt persevered and along the way became an expert in old buildings, building materials, architecture, historical and contemporary construction techniques and historic preservation. His is now a respected voice in the world of historic preservation, so much so that he has served as president of the Association for Preservation Technology International and frequently presents papers and gives talks to the preservation world both here and abroad.

He has become an expert on Guastavino vaulting, a specialized vaulting and terra cotta tiling technique used on self-supporting arches, such as those in the Buffalo Central Terminal. His first book, a biography of architect Rafael Guastavino, who developed the tiles and techniques, comes out next year.

Over the years, Diebolt has guided Vertical Access’s success. The list of buildings he and cohorts have inspected reads like a who’s who of historic landmarks: the U.S. Capitol, 14 (so far) state capitols (a tricky process given the round, slippery nature of the gold domes), the Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, St. Thomas Episcopal Cathedral, the Fire Island Lighthouse, the Canadian Pacific Railroad Bridge in Niagara Falls, the Occoquan Dam in Virginia, Independence Hall, the Empire State Building and hundreds more.

To accomplish that he’s put together a team of rare individuals who possess the skill and the willingness to work several hundred feet off the ground with only two, 11-millimeter ropes between them and eternity, and also a knowledge of architecture, history and construction as well.

One Vertical Access partner, Kelly Streeter, is a licensed structural engineer, while the other partner, Evan Kopelson, is an architectural conservator. Technician Kristen Olson holds an MA in Historic Preservation Planning from Cornell, project manager Mike Russell is a restoration expert, technician Michael Patino is a registered architect, and technician Daniel Gordeyeva was a climbing instructor at Cornell and a Sustainable Studies grad from RPI. The newest member of the team is East Auroran Patrick Capruso, a former architectural ornamentation tech from Boston Terra Cotta.

All are climbers and are SPRAT (Society of Professional Rope Access Technicians) certified. Safety training is a constant process and quite effective; Vertical Access’s safety record in 27 years is clean. The business has grown so much that they maintain offices in New York City, Connecticut, Washington, DC, and Salt Lake City as well as in Ithaca.

Kent spent part of last week at the train station, enjoying not only the work of readying the old place for the restoration that will transform it into a safe, wonderful event space unlike any in the Buffalo area or beyond.

“Evan, Patrick and I were commenting during work last week on what a great project the Central Terminal is, as well as how satisfying it is to be part of an effort to save such a grand and important building. I remember bringing my grandmother (Marion Brewer) here to pick up her sister, my Aunt Etta, when she visited from Philadelphia, so it’s especially poignant for me in that I have early childhood connections to the space.”

But the week in his hometown wasn’t all work and no play. It turned out that he had a free day before he left town, so I took him on a tour. We strolled Larkinville where a once desolate neighborhood now boasts breweries, restaurants, parks, concert stage, start-up businesses, and loft housing for the twenty and thirty-somethings who are making this city young again.

Then, we headed to the Small Boat Harbor to catch up with our longtime friend Captain Curt Etzel and his 16-foot runabout, Camo Yacht, that would be our waterborne limousine for the rest of the day. We motored the Buffalo River from Solar City along the shipping channel to the Peace Bridge taking in Silo City, Ohio Street, Riverworks, Canalside, the Naval Park, Erie Basin, the Buffalo Yacht Club and West Side Rowing Club in between, reliving Buffalo’s past and catching glimpses of its future along the way. While, for most of us, such a tour evokes feelings of nostalgia and hopefulness, for Kent, it made him wish he’d brought ropes, harness and his climbing gear. The Buffalo River is rife with historic buildings just aching to be evaluated by Vertical Access and considered for restoration. He hasn’t lived around here in a long while, but his heart hasn’t strayed too far.