April 13, 2024

What Happens After a Highway Dies

The redevelopment of Rochester’s Inner Loop was widely hailed as a model for repairing cities scarred by freeways. But the project’s next phase stands to take a different turn.

There’s an unmistakable sense of ambition in the freshly paved streets along the southeast end of downtown Rochester, New York, where a strip of new development has emerged on six acres of land created by the removal of a multi-lane expressway.

Turn off Union Street — the street-level boulevard that replaced the below-grade Inner Loop — onto the newly established thoroughfare dubbed Adventure Place and you’ll see a hotel and gaming cafe leading to four-story apartment buildings and a strikingly modern museum. It’s all part of a branded development called the Neighborhood of Play, anchored by the Strong National Museum of Play, a 375,000-square-foot interactive attraction that opened in 1982 and recently completed a $75 million expansion.

“If you’re familiar at all with what was the Inner Loop, then it is surreal when people come back to town,” says the city’s deputy commissioner of neighborhood and business development, Erik Frisch. “They’re like ‘Where am I?’ While people who have never been here before are like, ‘What do you mean there was a highway here?’ That’s the goal.”

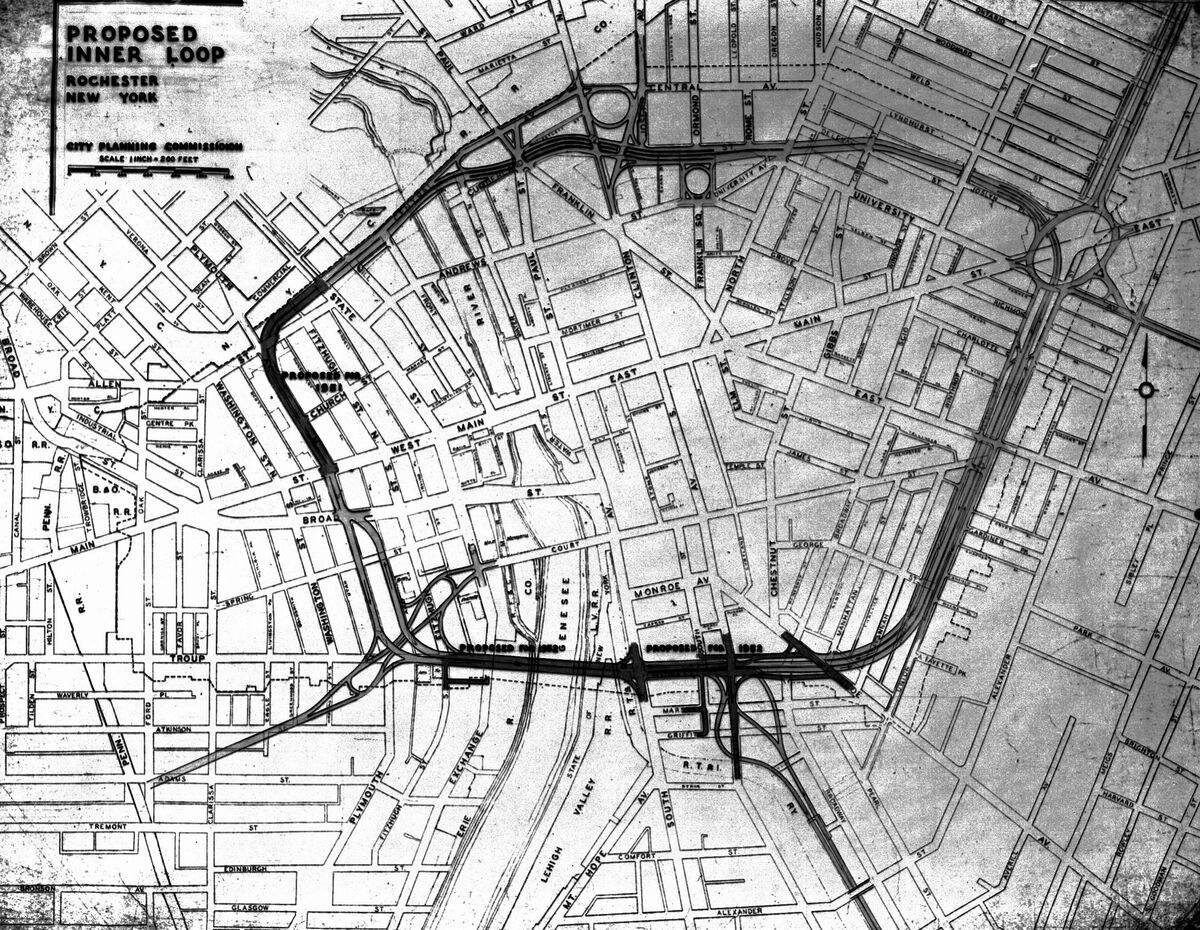

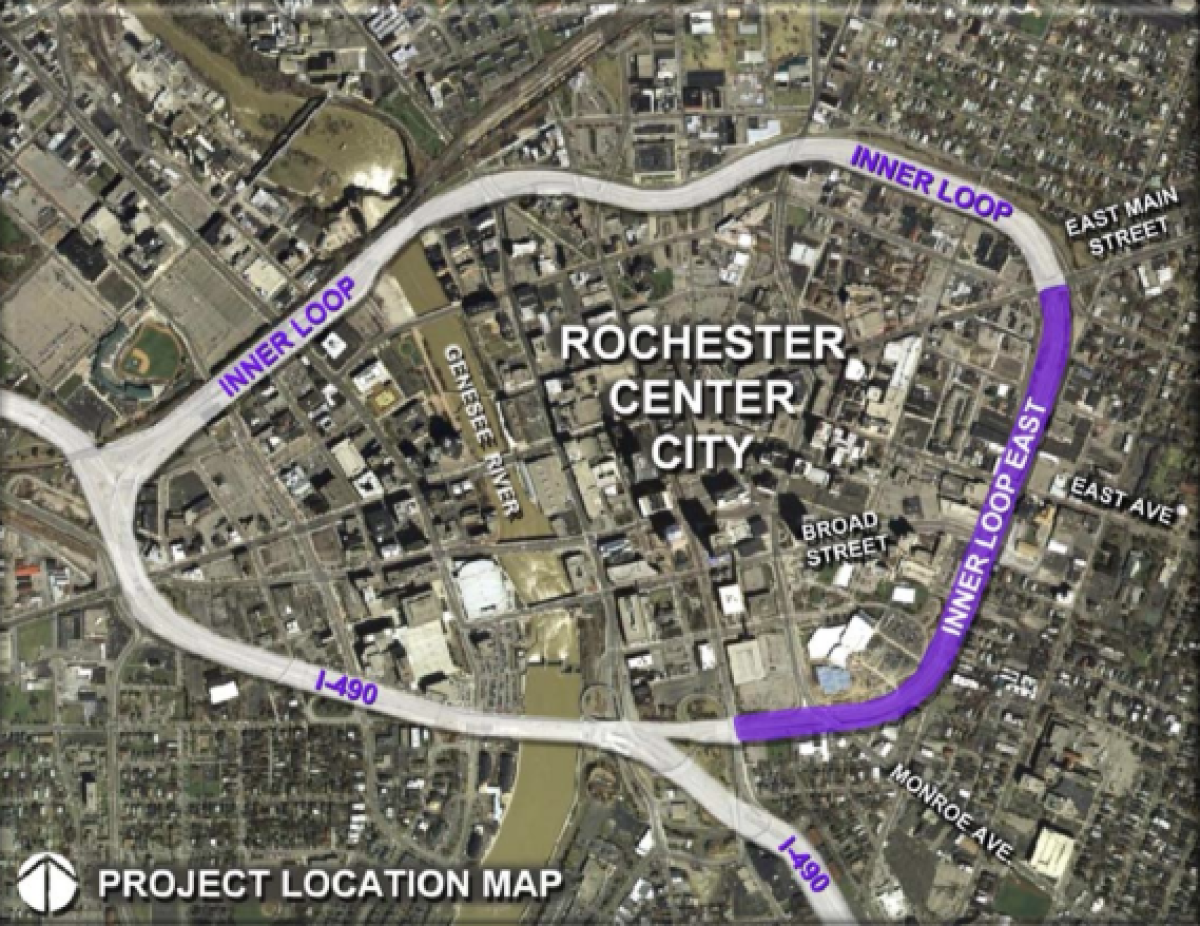

Completed in 1965, the Inner Loop once encircled downtown Rochester. But decades of population decline undermined its usefulness, and for residents of adjoining neighborhoods, the trench holding its six lanes functioned as a moat around the core of the city; local leaders eyed it for removal as early as the 1990s. In 2014, the highway’s least-utilized eastern segment was closed to traffic and the city launched a $21 million public works project to fill in the freeway’s footprint.

Today, the footprint of the highway removal project known as Inner Loop East looks like a checklist of 2010s US urban design priorities: Bulb-outs, protected bike lanes, apartment buildings with varied brick facades, first-floor retail and landscaped sidewalks hug the downtown side of Union Street. Planning is underway for the next phase of the project — a 1.5-mile-long stretch of still-operating highway referred to as Inner Loop North. Shovels are scheduled to be in the ground in three years.

Several US cities are eager to follow in Rochester’s footsteps, using federal dollars from the US Department of Transportation’s Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program to remove or build caps over urban highways. In cities like New Orleans and Baltimore, these efforts are positioned as a means of undoing the damage that automotive infrastructure did to poor and working-class Black neighborhoods. Elsewhere in upstate New York, Buffalo and Syracuse are both advancing plans to remove or partially cover especially scarring examples.

But it’s Rochester that is serving as a national model for how to actually get it done.

The city is also learning about the process along the way, as the second phase of the Inner Loop replacement won’t look like what has already been filled in. “Things have changed a lot in the time since we first started planning to remove the Inner Loop, locally and nationally,” says Frisch. “When we were talking about this project a decade ago, it was in economic terms, pure benefit cost: Remove this highway, generate investment, benefits outweigh the costs by more than 2-to-1.”

Now, the conversation is “much more socially oriented,” he says. “What impacts have these highways had on communities? What can be done to reverse that? How do we heal wounds and restore trust?”

Creating a New Neighborhood

The shape of the Neighborhood of Play, not mention its branding, owes much to its most prominent occupant, the Strong Museum. But the participation of the museum was not assured at first.

“They had a number of concerns,” says Frish. “It was already an important destination with a large surface parking lot along the frontage road to the Inner Loop, so it was very easy to get to and from the museum by the highway.”

CJS Architects, which led the Strong’s 2006 expansion, was asked again to help the museum out as the Inner Loop East project was becoming a reality. “It’s not a neighborhood business,” says Craig Jensen, principal at CJS. “They had been pretty protective of their parking lot and not interested in engaging with the rest of the city. We told them that if they’re going to make this work, they have to give up the parking lot, become part of the neighborhood, and really connect streets that are disconnected as a result of your property.”

On top of a $75 million, 90,000-square-foot museum expansion completed last summer, CJS and two local development partners worked with the Strong to create a series of developments that would be advantageous to them while also feeling like part of the reconnected community. Konar Properties built 238 apartments, over 100 of which are for people making between 60% to 80% area median income, while Indus hospitality group built a 126-room Hampton Inn hotel.

“Both are family-owned local developers,” says Strong Museum CEO Steve Dubnik. “We wanted to have people who were interested in and investing in the community.”

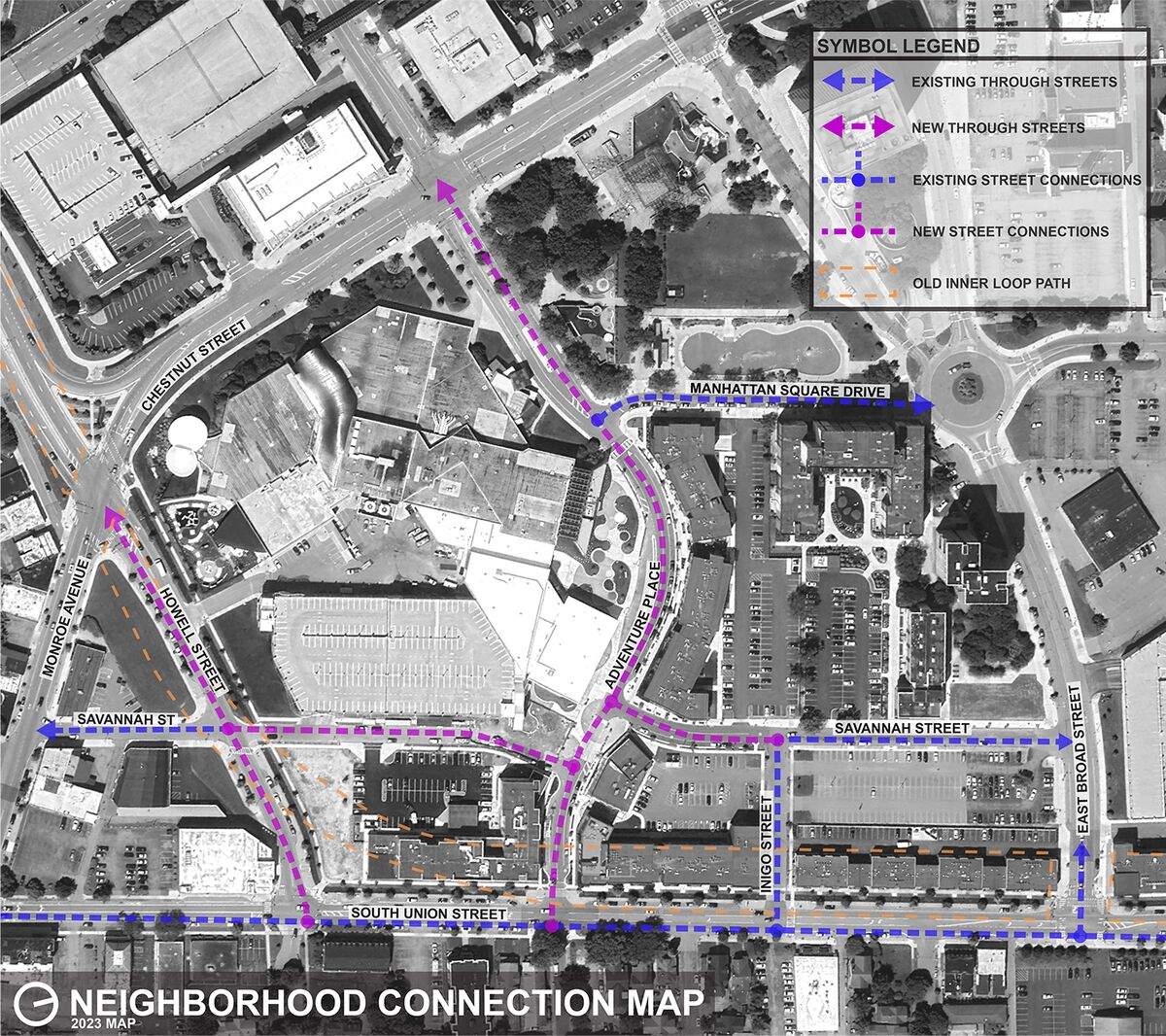

It wasn’t just the Inner Loop that was getting in the way of urban connectivity, Jensen says. The site around the highway had long lost its original street grid, as it had been reconfigured into a vast superblock defined by the Strong’s surface lot and a 1970s-era cluster of apartment towers.

“By getting the museum to commit to creating a neighborhood, we could cut through that superblock,” Jensen says. The developers threaded a new series of streets through the site. An eye-popping new parking garage for the museum also received $20 million from the state, doled out in increments tied to project goals like an increase in full-time employees, completing the museum expansion and building out the Neighborhood of Play.

“They really did deliver exactly what we had hoped was possible there,” says Frisch. “If they hadn’t chosen to be a good, community-minded partner, we probably would have a pretty disconnected, disjointed pattern over there.”

So far, the expansion has gone as planned for the museum. “We introduced a two-day ticket option and it has sold very well,” says Dubnik. “Many of those people are staying in the hotel and visiting the different locations around here. Our highest attendance prior to expansion was slightly shy of 600,000 in 2019. The new museum was only opened for half of 2023 and exceeded that record.”

The economic payoff of Inner Loop East has been considerable, according to the city: More than $200 million in new investment has been generated since the expressway was filled in. But the area’s urban fabric remains a work in progress. There’s still a lot of surface parking in the area, and traffic volume along Union Street is lower than anticipated. Bike and pedestrian activity has returned to pre-pandemic numbers and is expected to rise, however, and the new apartments have filled up, with Konar Properties reporting 95% occupancy. Commercial spaces are slowly finding new tenants, including a couple of bars and restaurants.

“It’s not on a major arterial, so it’s going to be a little tricky to run successful commercial enterprises there,” says Jensen. “There was a conscious attempt to concentrate the ground floor retail in a few buildings by the hotel and museum and try to activate the street with stoops and walkup apartments — other kinds of uses that can make the streetscape come alive without relying on commercial space.”

A few smaller, more challenging parcels remain undeveloped. The hotel was designed with enough room for an expansion, one small parcel may see a groundbreaking on a handful of walkup townhomes, and another is expected to see an approximately 60-unit affordable housing complex with first floor commercial space. “We’ve got some plans for ways to sneak in additional buildings on parking lots. But the parking demand will have to go down in order for that to happen,” says Jensen.

Take Two

After two years of study, Governor Kathy Hochul announced in 2022 that New York was committing $100 million to removing the last 1.5 miles of the Inner Loop’s northern stretch, opening up another 22 acres for development and public space. The scars of displacement and destruction are far greater here, where hundreds of homes and commercial buildings were demolished in a neighborhood called Marketview Heights.

“The Inner Loop truly went through and impacted the Marketview Heights neighborhood there in a way that it didn’t to the east,” says Frisch.

As a result, the emerging vision for what should be built there is being led by the community, rather than one cultural institution and its preferred developers.

Those along Inner Loop North’s path have also had plenty of time to think about what they don’t want repeated from the east. “There are a lot of good things about Inner Loop East — we really filled it in, we lead the nation in doing that. But we didn’t talk about reconnecting neighborhoods there,” says Suzanne Mayer, co-founder the local nonprofit Hinge Neighbors. “When you want to change something, you have to look at it differently than the status quo. Inner Loop East is the status quo.”

Mayer has some specific criticisms of the area, including its lack of green space and the large-scale, developer-driven new buildings. “They got rid of a moat, and built a wall.”

Hinge Neighbors, which Mayer runs with co-founder Shawn Dunwoody, has been leading the community’s planning efforts. The group’s leadership represents both sides of the highway: Mayer is a white woman living in Grove Place, just south of the Inner Loop; Dunwoody, a Black man, grew up to the north, in Marketview Heights. It’s a low-income area: A 2020 market analysis of Inner Loop North, commissioned by the city, found a median income of just over $16,000.

“We didn’t think that people [to the north] were going to be brought into the process as they should, because that was where all the harm had been done when they put in the Inner Loop,” says Mayer. “A lot of the people to the south are transplants, so it was really important to have the world know that a vibrant community exists in the north.”

“The conversations taking place with residents in Marketview Heights and their counterparts across the highway in Grove Place have been much more focused on outcomes,” says Frisch. “When we remove the highway, how is it going to benefit the residents that have been impacted by the highway, and the residents who will be impacted by its removal?”

Early attempts to get both sides on the same page were met with a shared skepticism about removing the highway at all. “We had a meeting with one group, and they said, ‘It’s a terrible idea. How will we get to the airport? And then on the other side they were telling us, ‘Oh, they [the city] are going to do whatever they’re going to do. How will we get to the mall?” recalls Dunwoody.

“One of the school administrators said, ‘We don’t need a park. We need parking for our teachers.’ We were like, ‘Oh my gosh, we’ve got a really long way to go,” says Mayer.

“All we could say was, ‘You don’t think this is good, but it is coming,’” says Dunwoody. “You should design the community you want to see for yourself, your children, and your children’s children. This is your opportunity to be involved.”

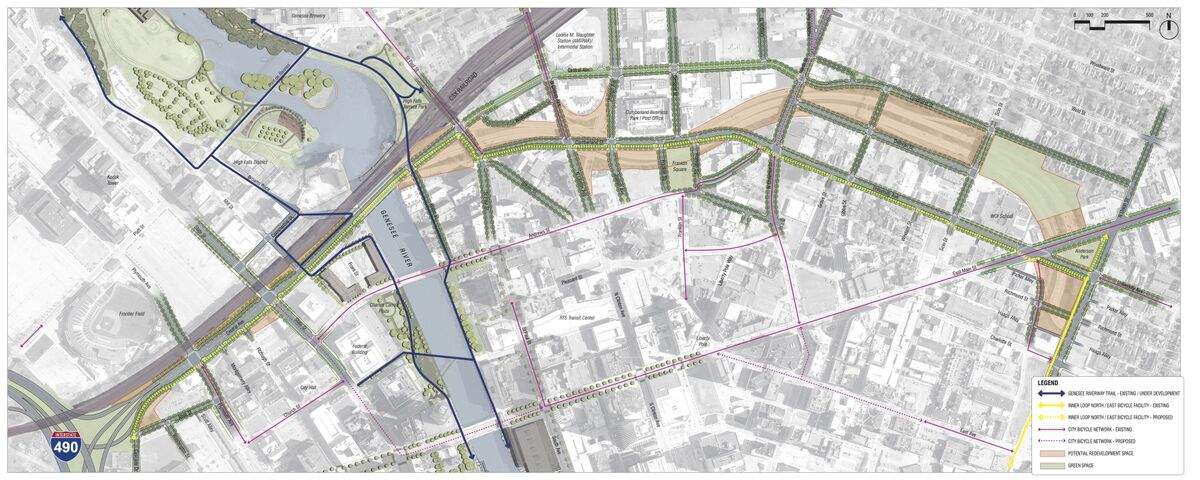

The city developed six different concepts for what the area would look like without the Inner Loop. The community settled on one anchored by a traditional grid layout. One of the most symbolic improvements is a full restoration of Franklin Square, a city park dating back to 1826 that had been split apart by the Inner Loop. “The goal is that you won’t know that there was a highway there,” says Frisch.

As for the development, it won’t look anything like what has been realized to the east. “Residents have said they don’t want to see large block development — they want lower density, affordable housing. Preferably owner-occupancy opportunities,” says Frisch.

That’s harder than getting a developer to build apartment blocks. When asked how the city can fill in these future parcels with single-family, owner-occupied homes for residents making well below the region’s median income of $62,000, Frisch emphasizes already-established access to state subsidies and city partnerships with philanthropic organizations and financial services. “We can bring the price point down,” he says. “We’re delivering affordable homeownership right now; new, single-family construction in the northeast quadrant of the city and soon a similar project in the southwest quadrant. We’ve done it. We’re confident that we can continue to.”

The project is now in an evaluation phase, which Frisch expects to have wrapped up by the summer. After that, preliminary design will take place for a year, followed by an environmental review, final design, and engineering. “We’re moving into the phase where the Department of Transportation takes over, and they aren’t always a friend to communities,” says Mayer. “Are they going to listen? Are they going to have engineers saying, ‘You can’t do that!’ Now we have to be very diligent.”

A Roadmap to Removals

To the east and west of Rochester, long-fantasized highway removal projects risk turning into disappointing realities as construction nears. In Buffalo, officials are determined to cap a section of the Kensington Expressway, but many nearby residents and activists feel strong-armed into a fast-tracked project with questionable benefits for residents in its path. And while the elevated section of Syracuse’s Interstate 81 is likely to come down, there are concerns that the community it ravaged will not be meaningfully restored.

Jensen says that the city’s experience redeveloping Inner Loop East should hold lessons for other cities. Union Street, for example, was rebuilt about one lane too wide. “But when I look at I-81, the street they’re putting back is more than double what it should be — it’s over the top,” he says, referring to the Syracuse project. “Return it to conditions that mimic the surrounding street grid and don’t feel as though you’ve got to still have an imprint of this highway. There needs to be a bigger vision.”

Mayer and Dunwoody’s group has been able to mold the Inner Loop removal plan into something that avoids a vision purely reflecting the expertise of traffic engineers and developers. “If you look at a place like Texas, their DOT is stronger than any city,” says Mayer. “We’re very lucky. We’ve had strong mayors; the last four or five really wanted this to get done. It’s important that the city stays in control. It’s our job to test that control, to push them.”

In an era of US urban planning where highway removals are becoming more common, the removals themselves are no longer seen as standalone triumphs. “There’s this idea that if you do it, it becomes something,” says Dunwoody. “No, you have to really think about what it is going to become. Does it create a new type of barrier or does it create new interactions? We know how to get a bunch of dirt in there. But can we get the connection right? That’s what people want to see.”

A map of the proposed Inner Loop from 1951, the year construction began. The circular freeway was supposed to relieve downtown traffic congestion. Credit: City of Rochester

A map of the modern Inner Loop shows the east segment, which got little traffic as the city’s population fell. It was closed in 2014 and replaced with an at-grade boulevard. Credit: City of Rochester

Union Street (foreground) is all that remains of the multilane Inner Loop highway; new development on its footprint includes a hotel. Photographer: Kim Smith Photo

A map of the area around the Strong Museum shows how new streets were arranged during redevelopment. Courtesy of CJS Architects

The rebuilt streetscape of the “Neighborhood of Play” is designed around pedestrian-friendly features. Photographer: Kim Smith Photo

The north section of the Inner Loop under construction in 1957. In the background, stands the 19-story Eastman Kodak Tower — then Rochester’s tallest building. Photographer: Ernest Amato. From the collection of the Local History & Genealogy Division, Rochester Public Library

Hinge Neighbors co-founder Shawn Dunwoody found that many local residents were skeptical about the highway removal. “All we could say was, ‘You don’t think this is good, but it is coming.’” Photographer: Arturo Hoyte

A concept map of the proposed removal of the north end of the Inner Loop shows how the original street grid could be rebuilt in the highway’s footprint. Credit: City of Rochester